Interdisciplinary Thinking

February, 2021

Good engineers are always good interdisciplinary thinkers. They can look across the scope of a project, visualize how the different components interact and apprehend problems before they occur. An engineering project can go from good to bad because of poor interdisciplinary thinking.

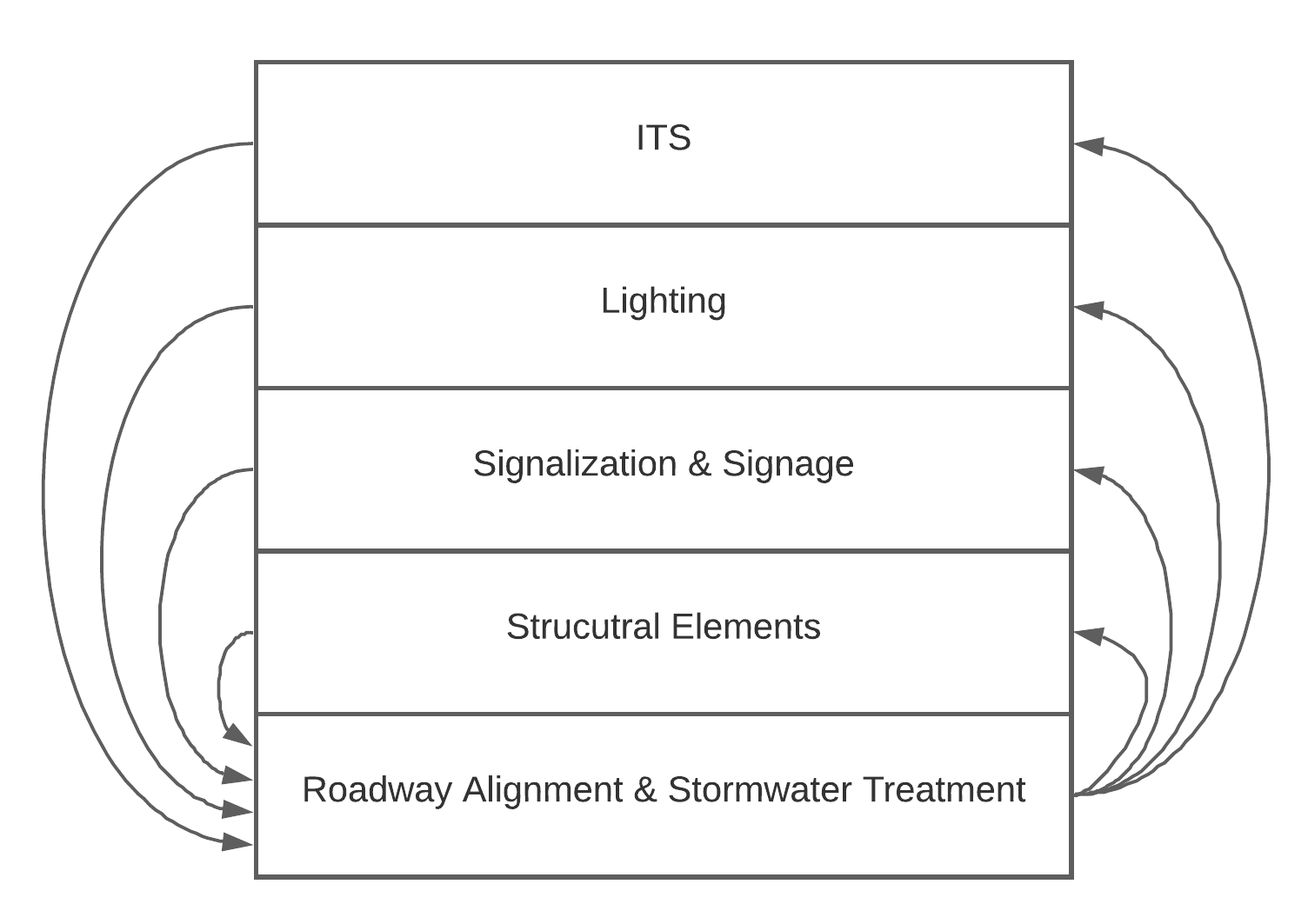

Transportation design projects involve two overarching disciplines Roadway Alignment and Stormwater Treatment. Everything else is a built on top of these two foundational disciplines. Imagine a rural road with two-lanes, two-directions, and some element for ensuring the stormwater runoff doesn’t flood the travelway. With that basic concept you build upwards as the situation becomes more complex. The first added complexity could be a simple span bridge crossing a stream. Another element could be safety lighting to illuminate a driver decision point which is indicated by a multi-post sign. The layers of complexity deepen but the concept of a roadway stays the same.

Now, imagine we are building this rural roadway and these engineering components don’t integrate. The drainage swale elevations don’t work with the roadway, the sign is not positioned to provide the driver adequate decision time, the light poles sit in the middle of the swales and the guardrail post run directly over sections of drainage pipe. This project would be a disaster to construct and cost the engineers dearly in claims.

But, how could a project like that ever make it to construction. Each of these issues has likely happened before on at least one project. I just put them together here as one nightmare situation. Low level integration slips through the cracks, but it doesn’t have to.

Can we become better at interdisciplinary thinking? Yes. For most people this skill is acquired unconsciously as they work on more projects. This process would happen over the years of an engineering career. However, I’m interested in accelerating the adoption of interdisciplinary thinking through formal steps. This way we all get better together, which improves the profession.

Early in my career I was fortunate to learn from engineers who encouraged this sort of thinking, without even knowing it. The common phrase was “Don’t look at the plans with blinders on.” This meant don’t just focus on your tiny piece of the project. Thinking with blinders on, hurts the outcome of any project because the conflicts show up during construction, when you have the least ability to affect the outcome.

Look up from your component of the project and visualize how your work affects the other components of the job. There are a two ways to do this. The first is to make an activity map (on paper or mentally) of all the other people that get affected if you change your design. If you are designing roadway alignments, who in your team must update their work, if you increase an elevation or shift an alignment. The second way to take the blinders off is to imagine you’re in the field with the plan sheets. Try to visualize building this part of the project with the information on the sheets. Would you need added details? Would you know if there was something below ground that you’d want to avoid? Now or in the future? Is your picture of the project complete?

Next, we need to get out into the field with the plans. Roadway and highway projects have deceptive optics from the plan sheets to the field. Your project that seems expansive on the screen could be smaller than you think. This can be a problem during construction when you need space for equipment or other field work.

While in the field you’ll also learn the balance between accuracy and precision. This topic is best covered in another essay but realize that specifications to multiple decimal places of precision are rarely meaningful in the construction of roadway projects. Although we need to be mindful of unnecessary precision, this does not excuse a lack a thoroughness. Highway engineering does require precision, but it isn’t titration. Remember, it’s a balance.

Developing construction staging plans will further develop your skill of interdisciplinary thinking. You’ll be forced to account for the demolition, installation, or relocation of all the items required to construct the project. This puzzle-building exercise often leads to designers rapidly growing in skill across disciplines. Learning the spacing requirements for excavation, crane placement or equipment sizes will quickly translate to design plans that apprehend problems before they’re sent to the field.

The three tasks of 1/ taking off the blinders 2/ visiting the field with plans and 3/ working on construction staging designs, will help any engineer get better at thinking across disciplines. This is a foundational skill that will improve project outcomes. The last way to improve this skill is to be curious. Infrastructure engineering is a broad field and the degree to which someone succeeds is tied to how much they’re willing to chase their curiosity and learn about the different disciplines. Seek opportunities to learn about the different disciplines in the knowledge stack of engineering and your thinking skills will inevitably improve.

Action Item: Take off the blinders. Get out into the field. Think like the contractor. Be curious about different disciplines.